Education

I want to see bright young people who engage with society's challenges be produced in numbers unseen before. I want these bright young people to be energized and happy that there are challenges for them to solve and to revel in the opportunity to solve them.

To achieve this I believe we have to turn education on it's head. To produce these bright young people we must make education engaging, challenging and fun. Engaged, excited students learn far better than bored ones. Students who see challenges as stimulating rather than frightening become resilient and optimistic. They internalize that the journey itself — filled with experimentation, struggle and curiosity — is it's own reward.

There are few things more inspiring than watching a student "switch on", moving from passive spectator to passionate participant. Imagine that being the norm. Switching on is universally good. It feels good for the students, it makes teaching more fun for the teachers and it produces better students who are more useful to society. Everybody wins.

It's difficult to measure whether someone is switched on. The best thing we have is a test for ability: PISA. All else being equal though we would expect engaged students to produce better PISA scores than unengaged students. I hope to see a stratospheric rise in PISA scores. Not because I like PISA scores, but because it's a decently good measure for how well we are doing on what really matters.

The challenge concretely

I believe facts are important. Even when they are uncomfortable — maybe even especially when they are uncomfortable. With that in mind, let's review the PISA scores.

OECD International Average PISA Scores (2000-2022)

Source: Wikipedia - Programme for International Student Assessment

The recent dip is probably just COVID, so let's ignore that and instead focus on what isn't there: a steady across-the-board increase in scores. Technology and information accessibility has risen significantly since the internet came along, but education outcomes are flat. The seriousness of this cannot be understated. Technology (and free market economics) is the engine we have used to transform sticks and stones into what we have today. Our lives today are quite literally paradise compared to almost anything that came before. It's paradise because everything that is important – life expectancy, child mortality, poverty rates, access to clean water, global literacy, food security etc. – gets better as technology gets better. The rising tide lifts all boats, but only if the boats aren't anchored to a specific height. Education seems to be anchored — we need to change this. That is, as technology gets better, so must education. Once we do that, education will keep improving and we get the outcomes we are looking for. It's simple, but not easy.

Uncomfortable truths

One curve that decidedly hasn't been flat over the last 20 years is Social Media consumption.

Facebook Monthly Active Users (Millions)

Sources: Meta Investor Relations and Statista

Social Media gets a bad rap. Well deserved. It also frequently gets a significant share of the blame for stagnating education outcomes. I think almost all of the arguments are valid and correct. Yes, the students are distracted by social media and yes, social media isn't exactly filling them with wisdom. Unfortunately, this criticism also gets used to hide a very uncomfortable truth. The truth is that Social Media has improved much, much faster than education has. Distracted teenagers don't scroll social media because they are distracted — they scroll social because they are bored. Social media is not the cause of distracted teenagers. We have had them since the dawn of time. Social media is a symptom of distracted teenagers, and if there were no social media, they would find other ways to be distracted — like throwing paper balls at each other or sending notes back and forth or any of the many things distracted teenagers have used as boredom outlets.

Obviously it isn't this cut and dry, but I think it's much closer to the truth than most people want to admit. Why do I think this? Because I know how social media is made. And I see how those lessons are not applied to education. It might seem an irrelevant detail, but I believe it's crucial to understand why students choose social media and not education when they are bored.

Mental models

It seems that most people's mental models of social media are something like this:

data capture + algorithm + optimize for engagement/outrage = highly successful social media.

This isn't wrong, it's just simplified to the point of missing the point. It's like saying that:

4 wheels + steering wheel + engine = car

Yes, that is part of a car, but it doesn't capture what a car is. Is this a car?

A car?

Most people think something like this when they hear car

A car.

If your mental model of what a car is is like the first image, you will also have difficulty understanding how it works and why it's parts (like the engine) have caused a societal revolution. Maybe it's just something people use when they are bored? If we take the time to truly understand social media and how it became successful, we can use those learnings to rebuild a much more engaging education system — an education that, like social media, gets better as technology gets better. This stands a real chance of producing bright, happy young people in much greater numbers.

Social media powder — just add water

The first and most important obstacle to understanding social media and how it's created is to understand that software in general is no longer designed and built — it's discovered by distillation. What I mean by that is that most people think of software much like they think of physical construction. Someone makes a blueprint and hands it off to someone else: "build this" and voilà. If this was accurate, we would still have software like in the 90s — blue screen of death and endless confusing menus almost as impossible to comprehend as the manuals that used to go along with any hardware appliance. Such software would be as distracting as those 90s hardware manuals. Not distracting at all.

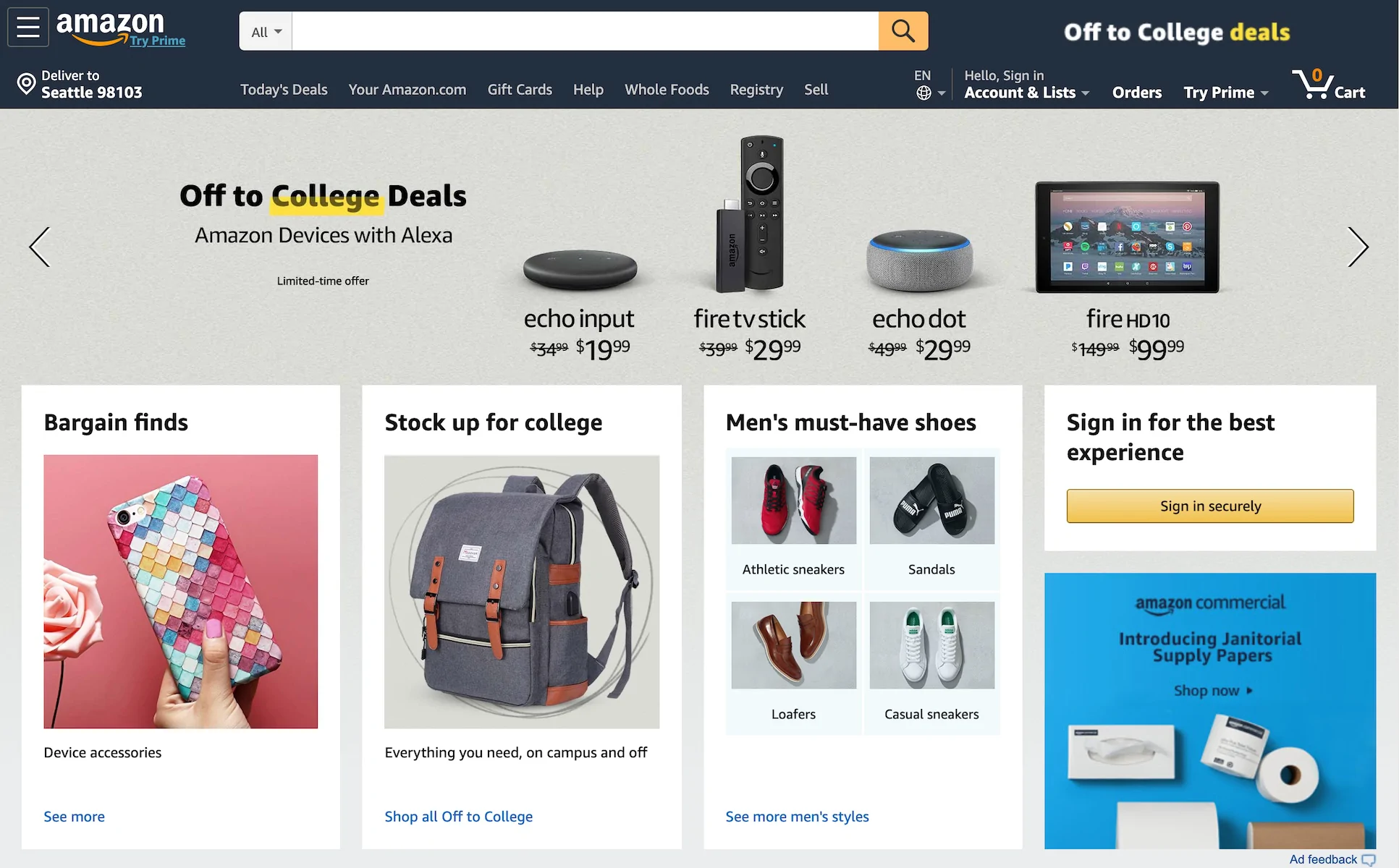

Social media today is nothing like that. It's incredibly simple and intuitive. Most people, without any manual, will know how to use it automatically. They are shepherded along a path that seems obvious and builds their confidence as they go along until they feel like experts. TikTok is a work of art. So stupendously simple, yet able to do almost everything you want it to. Most actions feel natural. Automatically surfacing just what you want, when you want it. None of those things are easy.

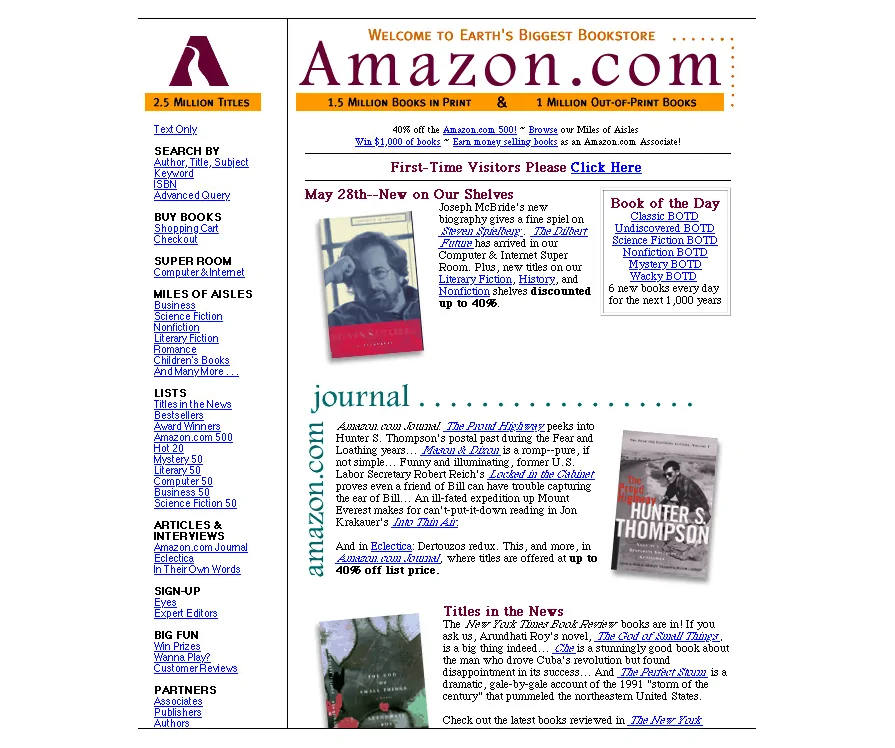

How did they get there? They started with something rough. Something that didn't work very well. They started with a simple recipe: flour + water + oven = bread. Then they made really bad bread. But instead of being discouraged by that, they saw that people liked bread despite it's problems. Then they got to work — they made improvements. Many, many, many, many improvements. This process of improvements is the work. It's 99% of the end result. Until you've been inside this process it can be difficult to understand just how transformative it is. Click the individual images below to see higher-detail versions.

Amazon 1997

Amazon today

This is just the visuals. Like an iceberg, the majority of the transformation is below the surface. This is what I mean when I say that software today is distilled — the result of thousands of small experiments that each either improve the product directly or produce knowledge used to guide the next experiments. Each of these experiments removes impurities and unnecessary fluff. It takes something promising but crude and turns it pristine. Education today is crude — it's filled with impurities and unnecessary fluff. This is why social media today is addicting and education is not. There are people who did the work to distill social media. This work hasn't been done for education yet. We need to do this work.

How does this look for education?

By definition, I can't tell you.

Successful software today isn't designed and built — it's distilled. It's discovered through experimentation. I can tell you where we start — everyone can: we start where we are. I can tell you which experiments I would begin with. That's useful, but ultimately not very important. I can also point to tools that speed up iteration and have proven effective in similar domains — that's more important. But what happens at iteration 4,000 is as opaque as what happens 100 years from now.

Still, here are some initial guesses and directions:

- I think games will play a big part.

- I think a market place for lesson plans or student exercises will play a part (think Khan Academy and Amazon had a baby).

- I think realtime feedback on almost anything the student does will play a part.

A scenario

Students learn math by building a bridge in a virtual world. This world lives in an online marketplace where teachers can configure and remix it. Students collaborate to design the bridge with AI giving feedback as they go.

Maybe they start with a simple bridge that can carry one person. Then they scale it up to support several people, then a car, then multiple cars. Finally, they're asked to build the cheapest bridge that still meets the goal.

Each iteration builds on the previous one, requiring progressively more advanced calculations. Afterwards, each student takes a short quiz to assess both their understanding and their experience. The teacher can then review results — with help from the AI — and pick follow-up exercises for each student.

Ideally, this happens online in a tool like Zoom. That way, we can capture everything: What students say, what they do (or don't do), how they interact.

Even if only 1% of education happens this way, it would produce a flood of data. That data can tell us:

- When students are engaged

- When they're bored or frustrated

- When they're learning — and when they're not

And with that, we can run thousands of micro-experiments to optimize everything:

- How difficult should the task be?

- How much introduction is necessary?

- How long should it last?

- How many students should collaborate?

- What's the best sequence of activities?

- How do we best support a group that's stuck?

- How should the mathematical theory be presented?

- How can we ensure everyone participates?

Every variable we tune helps transform a crude version into something polished and engaging. Now imagine scaling that across all of education.

We're going to learn so much about what causes kids to "switch on" — and we can use that insight to improve the other 99% of education. I also believe we'll figure out how to unanchor education, so it can finally rise with the tide of technological progress.

Road blocks and challenges

It's easy to come up with challenges for this. Here are a few:

- How do we train and upskill teachers to help with this?

- How do we fund all of it?

- Won't there be resistance to so much change?

This is a deliberately short list. I don't want to understate the difficulty of what lies ahead — the challenges are enormous. But ultimately, I don't think it matters how big they are.

The modern human standard of living is absurdly improbable. Humanity has faced countless difficult challenges and come out the other side. These are just new ones. We will succeed — because we have to. The current situation is not sustainable. We must unanchor education.

Most importantly, we have to set an example. How can we expect our bright young people to develop resilience, optimism, and a love of learning, if we can't even muster it ourselves?

Join me

I don’t have all the answers. I’m not an educator or a policymaker. But I believe something better is possible.

But if any of this resonates with you, let’s build on it together. And if you think it’s wrong — even better. Challenge it. Help me see what I’m missing. Let’s figure out how to do better, together.

What kind of future are we handing to the next generation? And what would it take to hand them something better?